International Organization

International Organizationfor

Chemical Sciences in Development

Past Activities: Biotic Exploration Fund

Former IOCD Working Group: Biotic Exploration Fund (BEF)

For many years IOCD operated the BEF, which worked to encourage and facilitate the sustainable and

equitable exploitation of natural resources for local benefit in low- and middle-income countries

(LMICs) and for global benefit. Below we present some highlights from the work of this important

IOCD initiative and salute the scientists who contributed to its success: in particular the

leadership of John Kilama, supported by Michael Tempesta.

Natural Resources Exploitation

Exploitation of the Earth's physical and biological resources has always been a feature of human

activities, but the pace and extent of this exploitation have increased greatly in the last two

centuries driven by and feeding technology advances, economic growth and population expansion.

Many LMICs which have been mainly the source of raw materials such as minerals and primary

agriculture products now wish to reap the economic and developmental benefits of increasing

production and adding value to the materials through processing. At the same time, global concern

for the environment requires that all countries conserve their natural resources, engage in

sustainable development and not follow pathways that may lead to pollution, exhaustion of resources

and loss of biodiversity.

Some examples of key contributions of chemistry to these challenges include developing cleaner, more

efficient, less energy-intensive and less polluting extraction and refining methods for minerals;

methods for the recycling of inorganic and organic materials; and new substitute materials that can

be produced more sustainably.

Chemists in many parts of the world work on the isolation, structure elucidation and bioassay of

natural products. These studies have made exceptionally valuable contributions to human health and

wealth:

-

Overall, about a third of all currently used medicines are derived from compounds first

extracted from natural sources such as plants, bacteria and fungi. These include

antibiotics, anti-cancer agents, analgesics, tranquilizers, muscle relaxants and substances

in many other therapeutic classes.

- An example of a product found through ‘chemical prospecting’ is ivermectin, a fungal metabolite of highly complex structure which has been marketed for treatment of parasitic worm infections in animals and human beings. As well as generating US$ 1 billion in sales, its donation by Merck to the World Health Organization laid the basis for the treatment and prospective eradication of river blindness (onchocerciasis) in Africa.

- Products from Aloe plants have been very successfully commercialized to take advantage of their medicinal properties.

-

When a country links local scientific activity with local commercialization of the resulting

products — pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, or personal care products — the

country may gain revenue to benefit its people and the success of the process can serve as

an incentive for putting conservation measures in place.

- One example of the power of bioprospecting is Madecassol®, a drug used for more than 25 years to treat intense burns, leprous wounds, and inflamed ulcers. It was developed from chemicals produced by the plant Centella asiatica in an effort involving scientists at the Malagasy Institute of Applied Research in Madagascar. The institute has earned valuable royalties from the drug's sales.

- Another example is Nicosan, which was developed at the Nigerian National Institute for Pharmaceutical Research and Development. This plant extract has shown success as a treatment for sickle-cell anemia, where it may help to reduce episodes of sickle cell disease crisis associated with severe pain. The drug has been approved for sale in Nigeria, and its manufacturer is currently seeking approval in the US and EU.

Taking An Ethical Approach To Biotic Exploration

The exploitation of biological resources has become an area of particular concern. Conservation of

biodiversity is considered vital for long-term human survival because plants, animals and bacteria

can be the source of new nutrients, genes conferring resistance to crop pests, drugs for combating

diseases and much else. This implies that studies are undertaken globally to uncover these valuable

assets, but exploitation needs to conserve their stocks as well as ensuring appropriate rewards for

their owners. Countries which have some of the most valuable and diverse and least studied

biological resources — often LMICs — have sometimes experienced ‘biopiracy’

in which samples of plants or knowledge about their uses have been taken abroad and exploited

without benefit to the country of origin or to the local inhabitants whose indigenous knowledge has

been the key.

Valuable lessons have been learned from the experience of LMICs that have developed ways to meet

these challenges. One ground- breaking example has been that of Costa Rica, a Central American

country which covers 0.04% of the world's total land area, yet is believed to harbour about 4-5% of

the estimated terrestrial biodiversity of the Earth. In 1989, Costa Rica founded the Instituto

Nacional de Biodiversdad (INBio) to gather knowledge on the country's biological diversity, its

conservation and its sustainable use. In 1991, INBio instituted an innovative agreement with a

multinational pharmaceutical company, in which Merck was granted the right to evaluate the

commercial prospects of up to 10,000 plant, insect, and microbial samples collected in Costa Rica.

In return for these ‘bioprospecting’ rights, Merck paid INBio US $1 million over two

years, and provided equipment for processing samples and scientific training. Merck also agreed to

pay a royalty — to be shared equally by INBio and the Costa Rican Ministry of Environment and

Energy — on the profits of any future pharmaceutical product or agricultural compound that

isolated or developed from an INBio sample. Subsequently, INBio negotiated several further

bioprospecting contracts involving other partners than Merck, including Eli Lilly, with the result

that income from INBio's bioprospecting activities rose to about US$1 million per year.

The Costa Rica example demonstrates the possibility of conducting research to identify new medicinal

products from natural sources in an LMIC, in a way that preserves property rights, generates a

financial return and encourages capacity building.

Many of the lessons were taken forward in the International Cooperative Biodiversity Groups Program,

initiated in 1992 to make multi-disciplinary, multi-institutional awards to foster work on the three

interdependent issues of drug discovery, biodiversity conservation, and sustainable economic growth.

IOCD's Work In Biotic Exploration

In collaboration with Thomas Eisner (known as the "father of chemical ecology"), in 1995 IOCD

established a Working Group known as the Biotic Exploration Fund (BEF), to facilitate and catalyse

ethical bioprospecting worldwide. Initial funding to set up the BEF came from the US National

Academy of Sciences, the American Chemical Society, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur

Foundation, UNESCO and the Novartis Foundation for Sustainable Development. (For links, see the Funding page.)

The BEF has assisted several LMICs in Africa, Asia and Latin America to develop policies for

ethical, sustainable bioprospecting, helping establish the foundations for new products and

processes that will contribute to better health and economic development.

Bioprospecting links laboratory work on biodiversity by a country's scientists with local

enterprises, which bring to market products based on the scientists' findings. At the same time,

bioprospecting involves a commitment to conserving a region's biodiversity to ensure its survival

and usefulness for future generations.

IOCD's contributions to biotic exploration have included work in Latin America, Asia

and Africa. These have been aimed at stimulating interest in bioprospecting and facilitating

engagement of the local scientists and policy makers. They have often involved sustained engagement

over several years to support national initiatives. Examples of IOCD action include:

- Nepal:

In 1997, the Royal Nepal Academy of Science and Technology requested IOCD to assist them in

building local capacity for bioprospecting in Nepal. Assisted by a grant from the Novartis

Foundation for Sustainable Development, an IOCD scientist travelled to Nepal to join members

of the Nepal Traditional Medicine Promotion Group (TMPG) in a joint mission of several weeks.

- An initial workshop with the Traditional Medicine Promotion Group explained the process of drug discovery and outlined the operations and policies for bioprospecting.

- Visits were also made to relevant research laboratories and local private pharmaceutical, cosmetic and other manufacturing facilities based on biodiversity resources in Nepal;

- Interviews were conducted of government officials concerned with access to biodiversity resources, scientific research and promotion of biotechnology business;

- Information was obtained about traditional healers in order to learn about their resources and determine their capabilities;

- Discussions were held about follow-on and IOCD provided a small grant to the TMPG for implementation of local action, with a view that TMPG could serve as a basic component of a long-term programme for developing the capacity and infrastructure in Nepal for bioprospecting.

- South Africa: In 1996 South Africa's Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) and IOCD scientists cooperated in organizing a bioprospecting workshop with university researchers, traditional healers, and other organizations. Today, CSIR is pursuing a robust bioprospecting programme in full compliance with the UN Convention on Biodiversity.

- Kenya:

In 1998 IOCD cooperated with the International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology

(ICIPE) in Nairobi, Kenya, to establish a bioprospecting programme that continues to expand

and prosper. Follow-up since then with the Government of Kenya has led to the establishment

in 2011 of a national bioprospecting strategy supported by Sh10 billion funding.

- The strategy is spearheaded by the Ministry of Forestry and Wildlife and Kenya Wildlife Service and will provide structures and systems to effectively and efficiently manage and regulate bio-prospecting activities in Kenya. It will seek to tap the huge market of bioprospecting and generate wealth and knowledge for the country. An estimated 80 per cent of Kenya's population depends on biodiversity. The strategy will be implemented through enhancing institutional capacity and review of the statutory and regulatory framework for bioprospecting and also developing a system of bioinformatics and benefit sharing. Other elements include enhancing information access and developing a communication system as well as a financial and resource mobilisation mechanism for bioprospecting.

- The launch makes Kenya among the first countries in the world to have a bioprospecting roadmap after establishment of the Nagoya Protocol on access and benefit sharing.

- Kenya's Minister of State for Planning, National Development and Vision 2030, Hon. Wycliffe Oparanya said that implementation of the strategy will contribute to the achievement of the Vision 2030 development blueprint, through improved management of biodiversity that enhances the economic wellbeing of the Kenyan people. He stressed the need for the country to have a common vision on biodiversity management. “Management of Kenya's biodiversity is vested in various agencies which lead to overlaps and competition on limited resources. All these need to be realigned with the new constitution to avoid duplication and overlaps while also taking into consideration the emerging issues of global concern,” he added.

- The launch also saw an expert dialogue workshop for effective biodiversity laws that attract investments for economic growth.

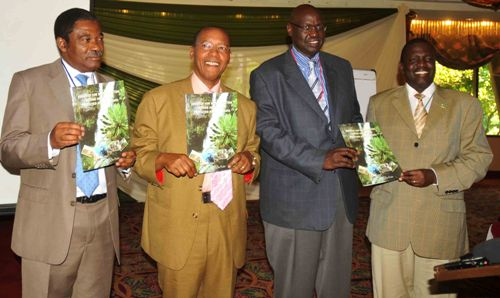

Launch of Kenya's new Bioprospecting Strategy

Launch of Kenya's new Bioprospecting Strategy

at the Safari Park Hotel, Nairobi on 3 November 2011Left to right: Mr. M.A. Wa Mwachai, Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Forestry and Wildlife; Hon. Mutula Kilonzo, Minister for Justice, National Cohesion and Constitutional Affairs; Dr. John Kilama, IOCD; Mr. Julius Kipng'etich. - Uganda: In 1998, noting the successful early progress of the Kenyan initiative, a group of scientists in Uganda contacted IOCD with a request for assistance to establish bioprospecting in their country. IOCD began a long-term programme to facilitate this. In April 2005, with IOCD cooperation, the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology convened the National Conference on Bioprospecting, entitled “Bioprospecting for Economic Development.” Recommendations of this conference called for establishment of the National Centre for Bioprospecting in Uganda. To facilitate passage of essential legislation on biodiversity by the Uganda parliament, in March 2007 at the request of the Uganda Minister of Planning IOCD convened a consultative briefing with members of Parliament, university vice chancellors, entrepreneurs and representatives of indigenous peoples. In a further follow-up, IOCD has been assisting Ugandan policy makers in the development of draft legislation on bioprospecting for parliamentary approval.

- Managing intellectual property (IP): The capacity to identify, negotiate and manage IP is crucial to a country's interests if it is to protect its natural resource, safeguard their use in ethical and sustainable ways and ensure a return on their value. IOCD has responded to recent requests from scientists and policy makers in East Africa with assistance in organizing training in IP. A planning meeting for IP training was held at the Kenya Wildlife Service headquarters in 2014 and further work on the training project is under way.

Further Information

In promoting bioprospecting, IOCD strives to comply with the UN Convention on Biological Diversity. Charles Weiss and Thomas Eisner, both of

whom helped to launch IOCD's BEF, discuss some of the challenges and useful strategies of

bioprospecting in their article "Partnerships for value-added through bioprospecting," Technology

in Society, 20, 481-498 (1998). For reprints, please contact IOCD.

The Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic

Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization to the

Convention on Biological Diversity is an international agreement which aims at sharing the

benefits arising from the utilization of genetic resources in a fair and equitable way, including by

appropriate access to genetic resources and by appropriate transfer of relevant technologies, taking

into account all rights over those resources and to technologies, and by appropriate funding,

thereby contributing to the conservation of biological diversity and the sustainable use of its

components. It was adopted by the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological

Diversity at its tenth meeting on 29 October 2010 in Nagoya, Japan.

Kim Lewis and Fred Ausubel have published a detailed analysis of strategies for bioprospecting

specifically aimed at developing antibacterials: K Lewis & FM Ausubel, 'Prospects for

plant-derived antibacterials', Nat Biotech 24(12), 1504-7, December 2006. The paper is

available here.

Jacques Gaillard and colleagues describe the work of the Malagasy Institute of Applied Research on

page 170 of the UNESCO Science Report

2005.

IOCD's John Kilama has co-authored a review of the value of natural biological resources as a source

of new medicines, in an important work co-sponsored by the UN Development Programme, UN Environment Programme, Secretariat of the

Convention on Biodiversity and World Conservation Union:

D.J. Newman, J. Kilama, A. Bernstein, E Chivian, Medicines from Nature, in E.

Chivian, A. Bernstein (Eds), Sustaining Life: How Human Health Depends on

Biodiversity, Oxford University Press, 2008, Chapter 4, 117-161.

Other useful literature on biodiversity and bioprospecting:

- Eisner, T. Chemical prospecting: A global imperative. Proc. Amer. Philos. Soc,

1994, 138, 385-395.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/986744?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents - National Biodiversity Institute (INBio) of Costa Rica.

https://www.gbif.org/grscicoll/institution/29acb160-1a5c-4c58-aba3-93093d60f642 - Weiss, C.; T. Eisner. Partnerships for value-added through bioprospecting. Technology in Society, 1998,

20, 481-498.

www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160791X98000293 - International Cooperative Biodiversity Groups program

www.icbg.org/ - Rosenthal, J. Integrating Drug Discovery, Biodiversity Conservation, and Economic Development: Early Lessons from the International Cooperative Biodiversity Groups. In F. Grifo. J. Rosenthal (Eds.). Biodiversity and Human Health. Island Press, Washington DC, 1997, Chapter 13. https://islandpress.org/books/biodiversity-and-human-health

Top of Page

Top of Page